In this ongoing series, we ask SF/F authors to describe a specialty in their lives that has nothing (or very little) to do with writing. Join us as we discover what draws authors to their various hobbies, how they fit into their daily lives, and how and they inform the author’s literary identity!

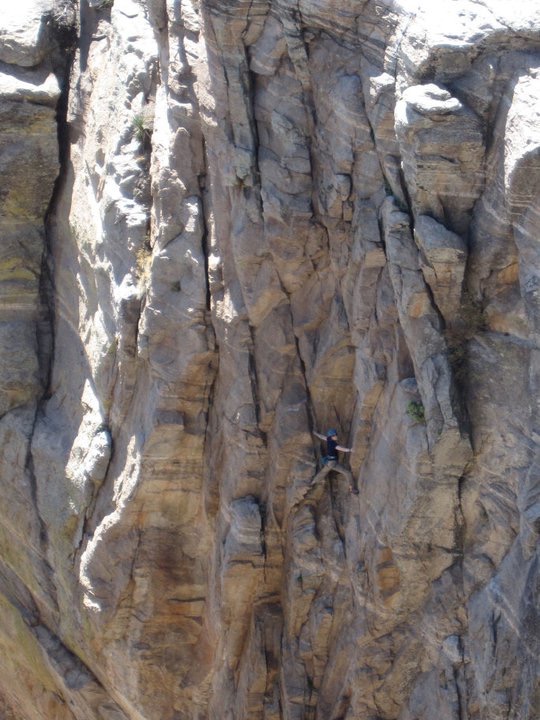

Fifty feet up, my hands start to shake. It is raining gently, and all around are mountains, helmeted with snow, soft in the valleys. But I don’t see them. All I see is the rock. One hand is wedged in a crack, bleeding under the thumbnail, and my other hand is folded onto a nub, just enough to give my first three fingers purchase.

There’s a bolt—a metal loop bored into the rock—right in front of my face.

I am about to fall.

So what? I try to tell myself. I won’t die. I am tied to a rope that is clipped into bolts along the length of my climbing route.

But my sense of self-preservation is not listening to the rational me. My sense of self-preservation really doesn’t want to fall. If I fail to attach my rope to this last bolt, I will fall. Six feet, my mind feverishly calculates. Another six feet after that. More. Ropes are stretchy. Also I will swing. It’s called doing a whipper.

“Hey Katherine, are you going to clip or what?” bellows my partner from below. “I’m going to sleep down here!”

“Jerk,” I mutter, quietly, so as not to disturb my precarious balance.

I gather my courage. I take a death grip on the rock with my left hand. I unfold my right, reach for the rope—

And fall screaming.

How did I end tumbling down an alpine cliff, with my partner joking callously below?

It started with a boy. Or rather, trying to impress a boy. His name was Alex, and his eyes were densely blue. When he climbed, you could see every muscle in his arms. I was entranced. On a whim, I decided to learn to rock climb too. Share his interests. Because that always ends well.

Some people are natural climbers. My crush and I went to an indoor climbing wall, and I discovered that I am not a natural climber.

Trying to ascend, I felt a hundred pounds heavier. My feet peeled off everything, my hands could grip nothing. I labored upwards, got sweating to the top of the simplest routes, and hung there, panting and clumsy.

I failed, utterly, to impress this boy.

But I was impressed. Not by Alex, who didn’t have much to say, however lovely his eyes. No, I was impressed by a girl with blond hair who climbed like a cat, joking as she did, her torrent of pale gold hair swinging behind her.

I realized, in short order, that I didn’t want Alex. But I wanted this girl’s grace, her confidence, the easy precision of her hands and feet.

So I started going to the climbing wall at odd hours, I grew calluses on my hands and wrenched my fingers. I took up weights; I attempted to do pull-ups.

Catlike grace eluded me. I thought about quitting.

One day, I went climbing outside. Climbing outside after climbing at a wall is a shock to the senses. A host of new sensations combines with the pure movement of just-get-to-the-top: the smell of earth and rock, the sounds of air and trees, and high places. Damp in crevices, sunbaked stone under your fingers. You get bruised, you get scared, you finish your day exhilarated, exhausted, and all your clothes have a permanent earth-metallic tang of rock.

That was when I fell in love. I no longer saw climbing as a means to get something else. No, I loved it for itself. Even the bruises. After that day, I went climbing every chance I could.

After college, I got a teaching assistant job in the Alps. The epicenter of sport climbing. I brought my shoes and my harness, hopefully. I met a kid named Paul, who had a rope and an obsession.

Up until then, I had gone on climbs with groups, content to follow on routes where more experienced climbers led. But that was not enough for Paul.

“You want to get up there?” he’d ask me, pointing to the top of some sun-drenched cliff. “Lead it yourself.”

Leading means you go first, clipping yourself to the crag as you go. Leading means falling, eventually.

It took me a long time to get up the courage.

One day I did. On an Alpine cliff, in spring.

I try it. And I fall.

The rope catches me with a jerk, and I hang there, swinging.

I lean back against my harness, fifty feet up, with mountains all around, and I shriek at the sky. I am shaking, but who needs to know that? I am alive. I have never been so alive. There is only air behind me, below me, above me. I am stranded in the sky.

I look down at Paul.

“Try again,” he tells me, grinning. “We don’t have all day.”

Top image: Frozen (2013)

Katherine Arden specialized in French and Russian literature, and has lived in Texas, France, Russia, and Hawaii—working every kind of odd job imaginable, from grant writing and making crêpes to guiding horse trips. Currently she lives in Vermont, but really, you never know. Her debut novel, The Bear and the Nightingale, is available from Del Rey.

Katherine Arden specialized in French and Russian literature, and has lived in Texas, France, Russia, and Hawaii—working every kind of odd job imaginable, from grant writing and making crêpes to guiding horse trips. Currently she lives in Vermont, but really, you never know. Her debut novel, The Bear and the Nightingale, is available from Del Rey.